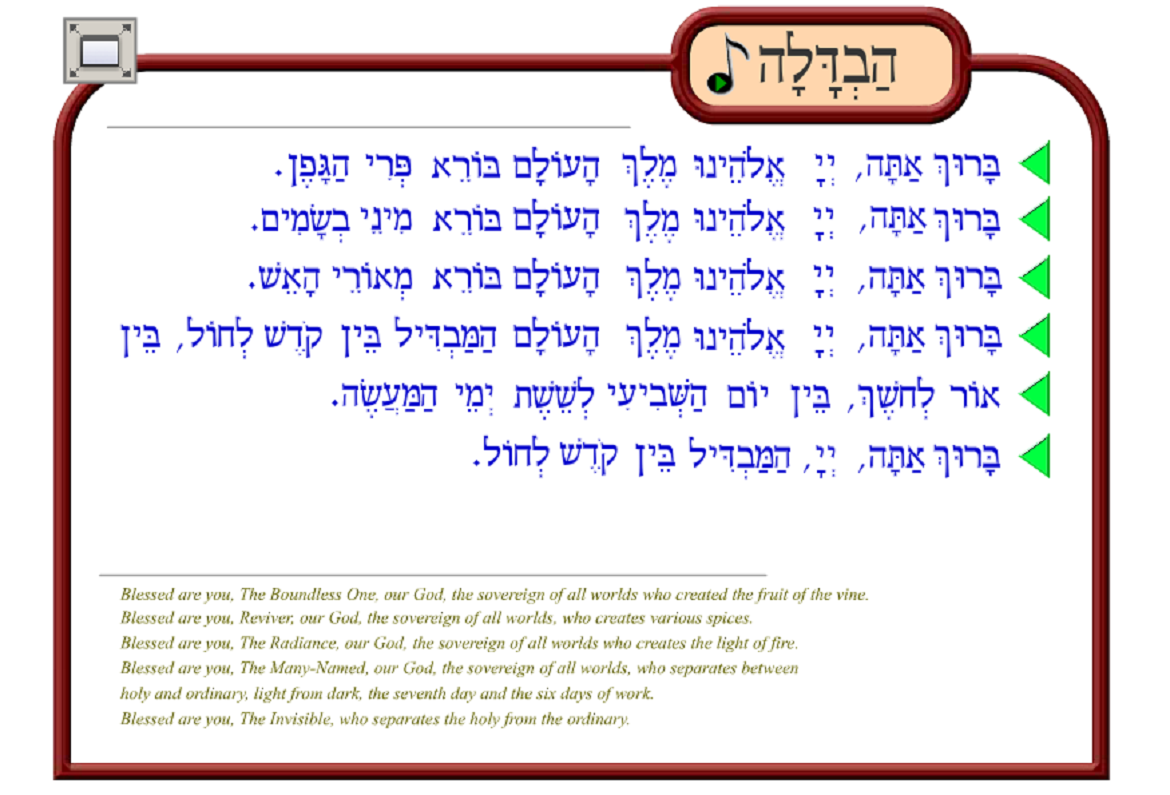

This post includes the Hebrew and English text of the Havdalah ceremony according to Reconstructionist tradition, as well as an explanation of the variations from the traditional text. To hear an audio recording, visit the Behrman House website and click on the green arrow (the small green arrow in the music note plays the recording of a man singing the whole ceremony, while the arrows at the beginning of each line play a slow recitation of that line.) The post also provides an introduction to the history, ideology, and practice of Reconstructionist Judaism, with an emphasis on the movement’s relationship to the concept of the Jews as the “Chosen People.”

Reconstructionist Havdalah

Textual Variations

The main textual variation in the Reconstructionist version of Havdalah is the omission of the phrase “…between Israel and the nations…” in the final blessing, which lists several different examples of how God separates between things on earth. Due to the movement’s rejection of the idea of “chosenness,” as explained below, this phrase has been omitted.

In addition, the English translation of the text presents many different descriptions of the Divine. While the Hebrew text is the same in each blessing, the English translation not only reveals many different interpretations of God, but also translates “melech” as “sovereign,” as opposed to “king,” to present an understanding of God that reflects gender equality and rejects patriarchal societal hierarchies.

Reconstructionist Judaism

Reconstructionist Judaism was developed by Mordecai Kaplan from the late 1920s to 1940s in America and gained popularity after the founding of the Reconstructionist Rabbinical College (RRC) in 1968. The movement, which was originally a stream within Conservative Judaism, views Judaism as a “progressively evolving civilization,” and does not demand adherence to a particular theology. It holds that Western secular morality has precedence over Jewish law and theology, yet it promotes many traditional Jewish practices as “folkways” (minhagim), or non-binding customs that can be democratically accepted, adapted or rejected by congregations in response to the changing needs of the Jewish people.

Jewish movements in America struggled to redefine Jewish identity and practice in the face of modern American culture. As opposed to ethical monotheism, Jewish law, or nationalism, Kaplan held that Jewish peoplehood was the sole constant throughout Jewish history, rejecting central concepts such as belief in a supernatural God, the divinity of the Torah, and the notion of the Jews as a “chosen people.” These ideological changes were reflected in the first Reconstructionist Shabbat Prayer Book, which appeared in 1945.

Choseneness is the belief that the Jewish people were singularly chosen to enter into a covenant with God, a concept which is deeply rooted in biblical verses and has been developed in Talmudic, philosophic, and mystical Judaism. While most Jews hold that being the “Chosen People” means that they have been place on earth to fulfill a certain purpose, it has often been misinterpreted as a racist ideology by Jews and non-Jews alike. Kaplan advocated dropping chosenness to avoid these accusations and because it went against modern Western thought to see the Jews as a divinely chosen people.

Today’s Reconstructionist institutions are based on Kaplan’s original principles, including democracy, egalitarianism, values-based decision-making, and inclusivity.